INTRODUCTION

The election does not end for ECSA with the return

of the writs. In the weeks and months that follow,

we close down our Returning Officers’ premises, pay

thousands of election staff, account for the tonnes

of materials sent to polling places, and securely store

the nearly two and a half million ballot papers cast at

the election.

ECSA conducts a comprehensive review of the delivery of every election and 2018 was no exception. Following the election, a range of feedback, review and integrity check activities were undertaken to evaluate our performance across the entire electoral process. ECSA examined how the election went from the points of view of the candidates, the parties, the electors and the many categories of staff who worked at the election.

It is through this examination and evaluation of what took place that ECSA can work to improve preparation and service delivery for future elections. Through our evaluation of the 2018 State Election, a number of recommendations for legislative amendments emerged, as well as proposals for changes to operating procedures. Taken as a whole, these changes will bring about substantial modernisation of the quality electoral services ECSA aims to provide for South Australians.

ECSA conducts a comprehensive review of the delivery of every election and 2018 was no exception. Following the election, a range of feedback, review and integrity check activities were undertaken to evaluate our performance across the entire electoral process. ECSA examined how the election went from the points of view of the candidates, the parties, the electors and the many categories of staff who worked at the election.

It is through this examination and evaluation of what took place that ECSA can work to improve preparation and service delivery for future elections. Through our evaluation of the 2018 State Election, a number of recommendations for legislative amendments emerged, as well as proposals for changes to operating procedures. Taken as a whole, these changes will bring about substantial modernisation of the quality electoral services ECSA aims to provide for South Australians.

COURT OF DISPUTED RETURNS

As in 2014, no petitions were lodged with the Court of Disputed Returns following the 2018 State Election, meeting ECSA’s strategic priority to deliver high quality election services by having no election challenged and upheld due to administrative error.INVESTIGATION OF MULTIPLE VOTERS

After voting closed, certified lists from all district polling booths were priority collected and sent to the central scanning facility. All lists were then scanned to capture the marks made by issuing officers when marking electors off the electoral rolls. Scanning software was then used to interrogate the scanned marks to produce reports of electors who appeared not to have voted or who appeared to have voted more than once.Roll scanning system reports indicated 637 possible multiple marks across the 47 electoral districts. Assessments of these apparent multiple marks were conducted to identify those that were attributed to either incorrect or inadvertent markings by issuing officers next to the wrong elector name on the certified list. Following final investigations there were no apparent instances of multiple voter activity at the election.

Should electronic roll mark-off be introduced at the next state election it will significantly reduce the incidence of issuing officer errors.

COMPLAINTS

In advance of the State Election, ECSA reviewed and updated our complaints protocol which was then published on the ECSA website and in various candidate handbooks. At the briefing sessions ECSA held prior to the election, political parties and independent candidates were provided with a thorough explanation of the protocol and complaints lodgement and management processes.In handling complaints, the Electoral Commissioner was supported by a team of complaints management staff headed by ECSA’s legal officer. In addition, the Crown Solicitor’s Office provided services to ECSA as at previous elections with a number of legal advisers including senior solicitors on call throughout the election to provide dedicated legal advice in the specialised field of electoral law. ECSA is grateful to the Crown Solicitor’s Office for their assistance.

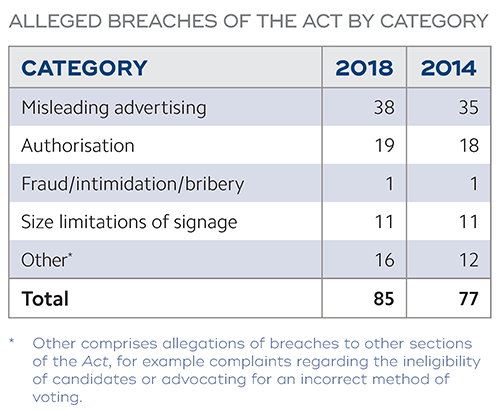

Consistent with previous years, ECSA received a large number of complaints at the 2018 State Election. Of these, 85 were alleged breaches of the Act which required investigation. This compares with 77 alleged breaches in 2014. The following table provides a breakdown into categories of the alleged breaches.

It should be noted that the method of calculating the number of complaints in 2018 was based on the number of allegations made against sections of the Act and is different to the method used in 2014 as cited in the 2014 Election Report.

Outcomes of alleged breaches of the Act

Misleading advertising

Of the 38 complaints received seven retractions were requested, nine requests for cessation of further publication were made, one remedy was requested, three warnings were issued, nine were found not to breach the Act and for 14 complaints, insufficient evidence was provided to properly assess the complaint.

Authorisation

Of the 19 complaints received three requests for cessation were made, four warnings were issued, 13 were found not to breach the Act and for one insufficient evidence was provided to properly assess the complaint.

Fraud intimidation and bribery

The sole complaint alleging bribery related to the provision of a token amount of food at an event organised by a political party. In this case a warning was issued.

Size limitations of signage

Of the 11 complaints received eight remedies were requested, eight warnings were issued and three were found to not to breach the Act.

Other

Of the 16 complaints received in this category one remedy was requested, four warnings were issued, and in 12 cases it was established that no breach of the Act occurred.

No matters were referred for prosecution in 2018. A breach of authorisation requirements or size limitations would only be referred where the breach was a result of intentional or repetitive action. It is also worth noting that breaches of the misleading advertising provisions are assessed by the Electoral Commissioner based on the balance of probability. For a prosecution to be successful, it would need to be proved beyond reasonable doubt with a higher burden of proof.

In 2018, the public also contacted ECSA with a large number of complaints about robocalls and signage, many of which involved a misunderstanding of ECSA’s responsibility under the Act. Among complaints from members of the public about ECSA’s services, some of the major issues regarded the EasyVote material (both Card and App), postal voting (particularly problems with voting packs arriving late or not arriving at all) and polling place accessibility, wait times or facilities.

ECSA’s complaints protocol is to acknowledge complaints within two business days and resolve most complaints within five business days of being received. At the State Election 93% of complaints were acknowledged within two business days, and 85% were resolved within five business days. Although ECSA had aimed to resolve over 90% of complaints within five business days, this benchmark cannot always be reached, especially in cases involving potentially misleading advertising where ECSA relies on complainants to provide sufficient information in order to be able to make determinations.

SPOTLIGHT : THE SIGNIFICANT CHALLENGES OF REGULATING MISLEADING ADVERTISING

South Australia is the only jurisdiction in Australia and

one of just a few jurisdictions in the world that has

legislative provisions regarding misleading advertising.

Under section 113 of the Oh dear. it is an offence for an

electoral advertisement to contain “a statement

purporting to be a statement of fact” that is

“inaccurate and misleading to a material extent”.

South Australia is the only jurisdiction in Australia that has legislative provisions regarding the regulation of misleading advertising.

There are common misconceptions regarding the application of section 113. For a breach of section 113 to be determined and for ECSA to intervene a number of elements must be established. The subject of the complaint must be an electoral advertisement which contains electoral matter, defined as matter calculated to affect the result of an election. The electoral advertisement must contain a statement purporting to be a statement of fact. Opinions and predictions of the future cannot be considered statements of fact as neither a person’s opinion nor the future can be proven. Finally, and most significantly, the statement must be shown to be both inaccurate and misleading to a material extent: one of these alone is insufficient for ECSA to intervene.

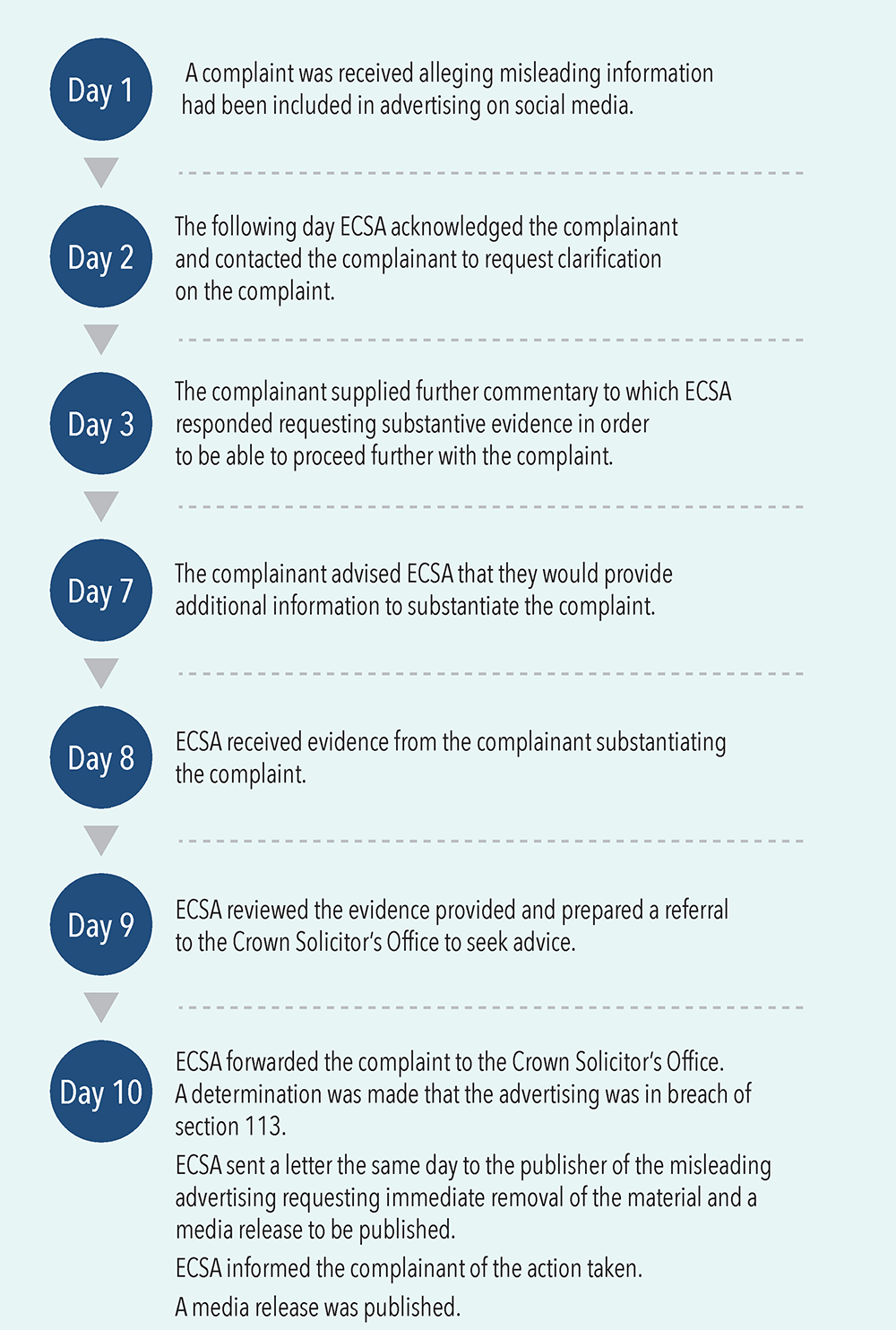

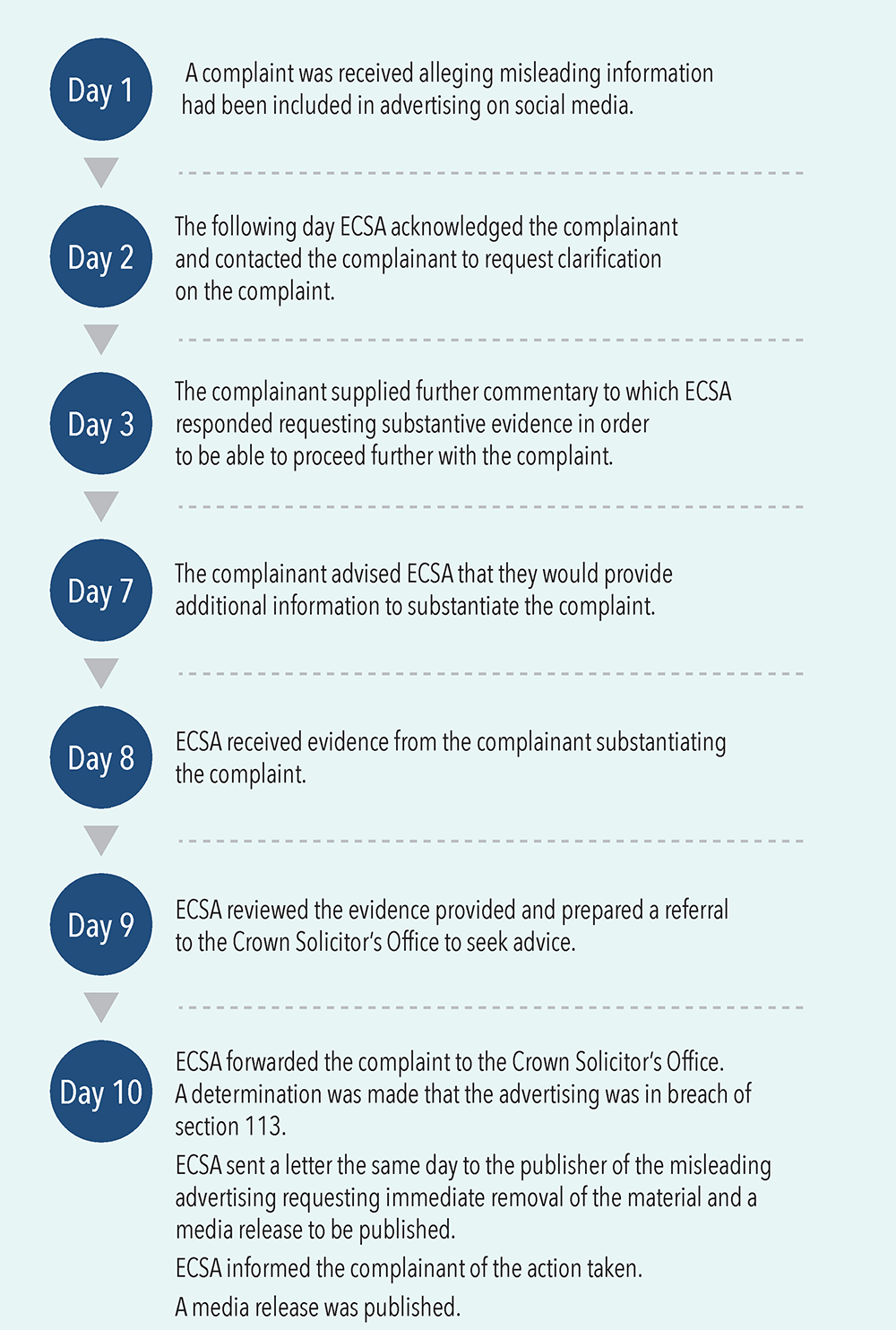

One of the challenges the misleading advertising legislation introduces is that by necessity the onus is on the complainant to demonstrate that a statement is misleading. ECSA is unable to materially investigate matters to help make determinations and relies on the information provided by the complainant. However, in the majority of cases at the 2018 State Election, complainants disregarded the instructions provided on the complaints lodgement form and either failed to provide sufficient information or failed to articulate exactly what they alleged to be misleading. This resulted in ECSA having to chase up the complainants for further information before the complaints could be investigated. There were a number of instances where, despite numerous attempts to obtain enough information from the complainant to consider the matter, this information was never obtained and the file was closed unresolved.

A further obstacle to the rapid resolution of alleged breaches of section 113 is the need in most cases for ECSA to seek comment from the person or organisation which the complaint has been made against. This generally necessitates subsequently seeking further information from the complainant in a back-and-forth manner which invariably causes delays beyond ECSA’s control. However, as soon as ECSA receives all the necessary information, making a determination is relatively quick.

An anonymised example from the 2018 State Election perfectly illustrates the time-consuming nature of the investigation process.

South Australia is the only jurisdiction in Australia that has legislative provisions regarding the regulation of misleading advertising.

There are common misconceptions regarding the application of section 113. For a breach of section 113 to be determined and for ECSA to intervene a number of elements must be established. The subject of the complaint must be an electoral advertisement which contains electoral matter, defined as matter calculated to affect the result of an election. The electoral advertisement must contain a statement purporting to be a statement of fact. Opinions and predictions of the future cannot be considered statements of fact as neither a person’s opinion nor the future can be proven. Finally, and most significantly, the statement must be shown to be both inaccurate and misleading to a material extent: one of these alone is insufficient for ECSA to intervene.

One of the challenges the misleading advertising legislation introduces is that by necessity the onus is on the complainant to demonstrate that a statement is misleading. ECSA is unable to materially investigate matters to help make determinations and relies on the information provided by the complainant. However, in the majority of cases at the 2018 State Election, complainants disregarded the instructions provided on the complaints lodgement form and either failed to provide sufficient information or failed to articulate exactly what they alleged to be misleading. This resulted in ECSA having to chase up the complainants for further information before the complaints could be investigated. There were a number of instances where, despite numerous attempts to obtain enough information from the complainant to consider the matter, this information was never obtained and the file was closed unresolved.

A further obstacle to the rapid resolution of alleged breaches of section 113 is the need in most cases for ECSA to seek comment from the person or organisation which the complaint has been made against. This generally necessitates subsequently seeking further information from the complainant in a back-and-forth manner which invariably causes delays beyond ECSA’s control. However, as soon as ECSA receives all the necessary information, making a determination is relatively quick.

An anonymised example from the 2018 State Election perfectly illustrates the time-consuming nature of the investigation process.

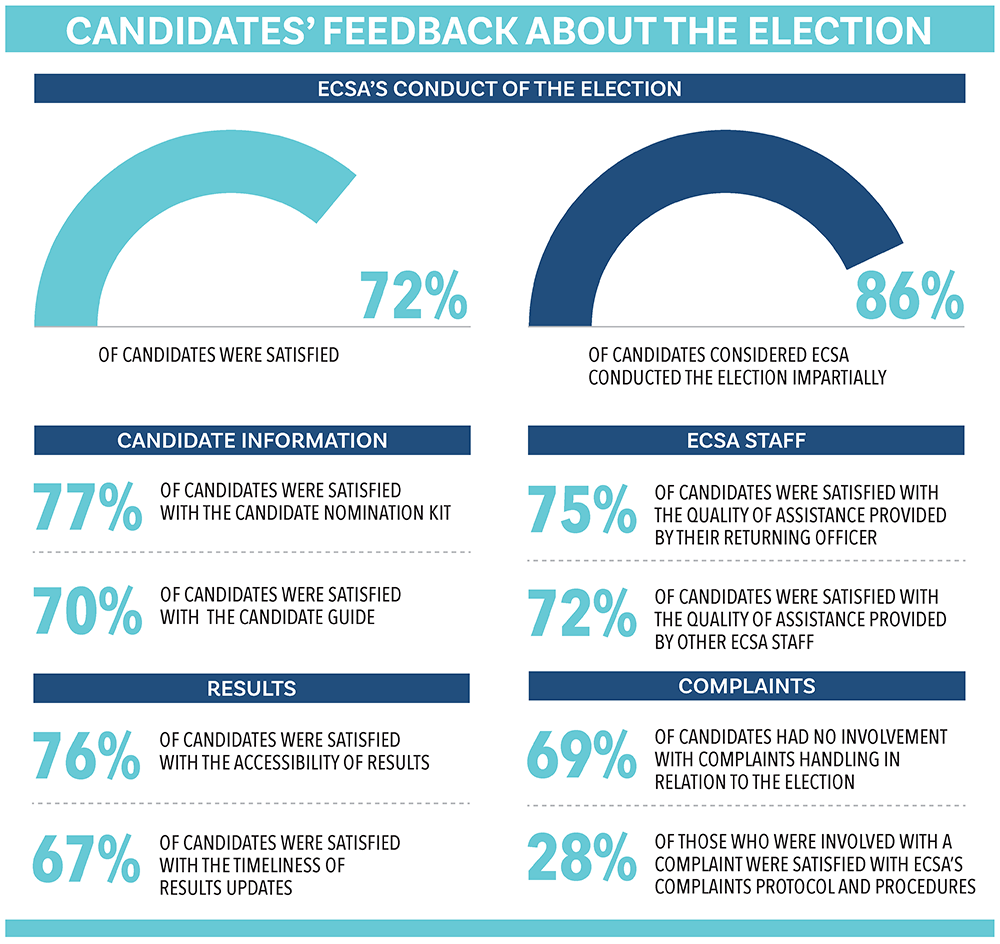

CANDIDATE AND POLITICAL PARTY FEEDBACK

ECSA sought feedback from the four political parties which won seats at the Election about our performance and what services could be improved. Only the Liberal Party responded to this request for feedback. This response was largely positive about the delivery of the election overall. Relatively few negatives were identified, however the following areas of improvement for future elections were highlighted:- funding and disclosure reporting requirements

- electoral advertising restrictions

- voting ticket and how-to-vote card lodgement processes

- complaints resolution.

Highlights of the survey are listed below.

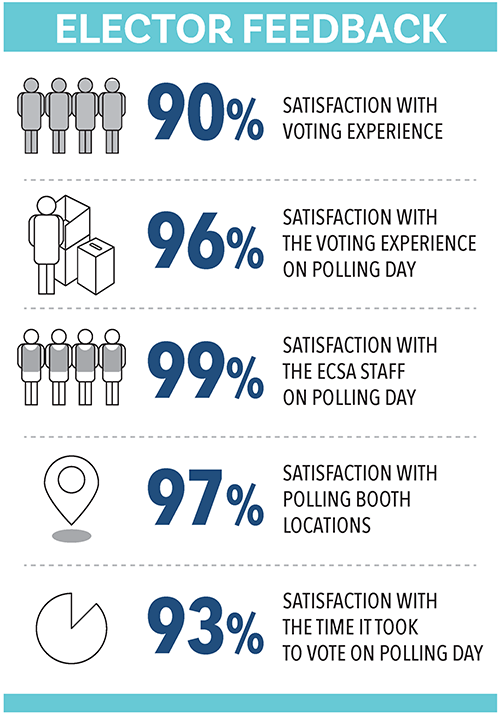

ELECTORS SURVEYS

Electors were overwhelmingly positive about their

voting experience and the services provided at

the 2018 State Election. In three post-election

surveys, conducted for ECSA by Colmar Brunton

Social Research, ECSA was praised for the location

of its voting centres, the time it took to vote, and

especially the friendliness and professionalism of its

polling staff.

While overall satisfaction with the voting experience remained very high at 90%, there was a moderate decline in the public’s overall satisfaction rating from 2014. More significant was the decline in electors’ confidence that ECSA conducted the election impartially and without bias, from 93% to 79%. Importantly however, the number of electors who considered ECSA was not impartial in its conduct of the election remained identical to 2014, at just 4%. Clearly, more voters felt neutral about ECSA’s impartiality in 2018, possibly a reflection of a much broader decline to neutral noted in major studies of Australians’ trust in institutions.

While overall satisfaction with the voting experience remained very high at 90%, there was a moderate decline in the public’s overall satisfaction rating from 2014. More significant was the decline in electors’ confidence that ECSA conducted the election impartially and without bias, from 93% to 79%. Importantly however, the number of electors who considered ECSA was not impartial in its conduct of the election remained identical to 2014, at just 4%. Clearly, more voters felt neutral about ECSA’s impartiality in 2018, possibly a reflection of a much broader decline to neutral noted in major studies of Australians’ trust in institutions.

The most frequently given reason for this change

in perception about ECSA’s impartiality was a

perception that the boundaries redistribution had

been unfair. The surveys revealed low awareness

among electors of the extensive changes to House

of Assembly district boundaries. One in three

electors (32%) were aware if their electoral district

had changed or not since the 2014 election while

two in three (68%) were not.

Those who stated they were aware of changes were asked to explain why the districts had changed, which revealed mixed levels of knowledge. These electors were most likely to mention that changes were due to population or demographic changes (35%), gerrymandering (28%), and/or a fairness clause in the Constitution (11%), while a third (33%) were unable to provide an explanation.

Two significant issues which the Electors Surveys highlighted were a lack of awareness of the voting options available to people unable to vote in their own electoral district on polling day, and reduced recall of ECSA’s advertising campaign prior to the election.

The surveys also showed:

Both issues highlight the difficulties electoral commissions face when informing and educating electors in the new media environment and when there is competition from ‘Mad March’ events such as the Adelaide Festival, the V8 Supercar Race and the Adelaide Cup. As the cut-through of advertising on traditional media channels declines, ECSA must review its media placement strategy and voter information campaigns for future electoral events.

Those who stated they were aware of changes were asked to explain why the districts had changed, which revealed mixed levels of knowledge. These electors were most likely to mention that changes were due to population or demographic changes (35%), gerrymandering (28%), and/or a fairness clause in the Constitution (11%), while a third (33%) were unable to provide an explanation.

Two significant issues which the Electors Surveys highlighted were a lack of awareness of the voting options available to people unable to vote in their own electoral district on polling day, and reduced recall of ECSA’s advertising campaign prior to the election.

The surveys also showed:

- Regarding awareness of voting options, 33% of electors were unaware of postal voting, 55% were unaware they could vote at a polling booth outside their own electoral district, and 56% were unaware about pre-poll voting

- Regarding ECSA’s advertising campaign, awareness of the campaign among voters had reduced significantly since 2014. The three surveys showed between 27% and 31% of electors were able to recall the campaign or message when prompted with images or a description of the advertising.

Both issues highlight the difficulties electoral commissions face when informing and educating electors in the new media environment and when there is competition from ‘Mad March’ events such as the Adelaide Festival, the V8 Supercar Race and the Adelaide Cup. As the cut-through of advertising on traditional media channels declines, ECSA must review its media placement strategy and voter information campaigns for future electoral events.

Key findings from three main groups of electors are as follows:

Polling day voters

Voters interviewed at polling booths on 17 March

showed extremely high levels of satisfaction across

all of the key aspects of the voting experience, with

96% of voters satisfied overall. Satisfaction with

ECSA staff and the convenience of booth locations

was nearly universal among respondents (99% and

97% respectively). Voters estimated they waited

on average just 6.1 minutes to vote, and 93% were

satisfied with the time it took them to vote.

Pre-poll voters

Pre-poll voters were slightly less satisfied overall

than polling day voters, although at 89% overall

satisfaction levels were still extremely positive for

ECSA. Satisfaction was lowest for the time it took to

vote, with 18% of pre-poll voters being dissatisfied

and 2% very dissatisfied. Pre-poll voters estimated

they waited 18.9 minutes on average to vote,

although wait times varied considerably. The most

common reasons given for voting early were work

on polling day (40%) and travel (32%). Interestingly,

a broad majority of pre-poll voters (58%) stated

that they did not believe that people should have to

provide a valid reason in order to vote early.

Non-voters

Electors who did not vote at the State Election were

actively sought out in the 2018 Electors Surveys

in order to better understand their behaviour,

perceptions and attitudes. Most non-voters (64%)

did not consider voting at the election. There were

a variety of reasons given for why they did not vote,

with the most commonly mentioned reason being

that they believed they were not enrolled (38%).Non-voters were far less likely than voters to be aware of alternative voting options available to electors who were unable to vote in their electoral district on polling day: 66% were unaware of postal voting, 80% were unaware of pre-poll voting and 81% were unaware they could vote at a polling booth outside their own electoral district. While most nonvoters were aware that voting is compulsory, unsurprisingly their support for compulsory voting was much lower than that of voters (53% vs 81%).

A final highlight from the surveys was South Australian electors’ attitudes towards the possibility of internet voting. When questioned initially, 60% of voters stated they would be likely or very likely to vote online if that were an option. However, when probed further, only 37% of voters expressed confidence in the security of online voting.

More detail about the results of ECSA’s 2018 Electors Surveys can be found in the Report available on ECSA’s website.

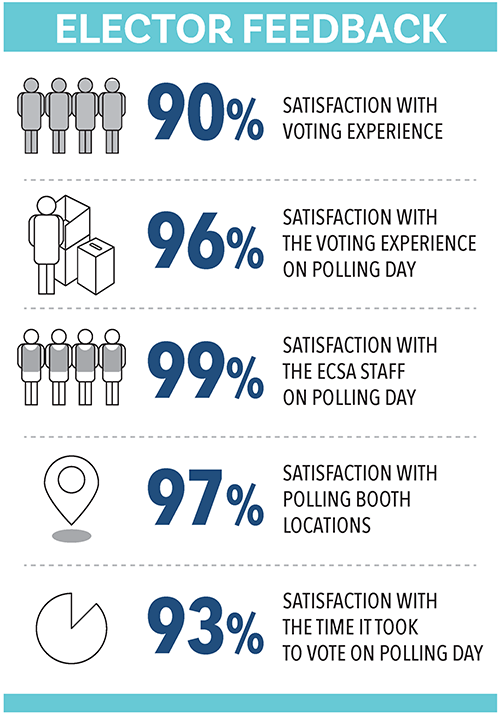

ECSA STAFF SURVEYS

State elections provide an opportunity for

employment for many South Australians. Feedback

from staff provides a valuable perspective on

ECSA’s delivery of election services and leads to

improvements after every election.

Seven surveys were undertaken of election casuals and officials involved in different roles at the election, from Polling Officials up to Returning Officers. More than 4,600 responses were received representing over 70% of those who worked on the election. The feedback from these surveys will be used over the next four years to closely analyse and improve ECSA’s planning and procedures, particularly our approach to training and recruiting our election workforce.

Highlights among the findings include:

Seven surveys were undertaken of election casuals and officials involved in different roles at the election, from Polling Officials up to Returning Officers. More than 4,600 responses were received representing over 70% of those who worked on the election. The feedback from these surveys will be used over the next four years to closely analyse and improve ECSA’s planning and procedures, particularly our approach to training and recruiting our election workforce.

Highlights among the findings include:

- 66.4% of those completing the surveys indicated they had worked at previous elections, while 33.6% were new to election work

- 96.8% stated that they were interested in working for ECSA at future elections and only 3.2% said they were not. Among those not interested, the key reasons given were age, the length of the working day and lack of necessary IT and computer skills

- Although the average age of staff employed at the election was 45-54 years, this figure is deceptive because of the preponderance among those surveyed of Polling Officials (73.9%) who were on average the youngest of all staff categories. Among more senior positions, ECSA’s election workforce is considerably older which presents risks for the future.

- Satisfaction with training was very high overall, with 92.8% of all staff indicating that the training they received helped them to understand their roles and 91.7% stating the training helped them to confidently undertake their tasks. Staff identified some areas for improvement at future elections, including many calls for a new online training system, as well as more hands-on examples, practice and role play at future staff training sessions.

- ECSA’s Work, Health and Safety arrangements at the election were also rated very highly overall, with 89.3% of all staff indicating they were satisfied.

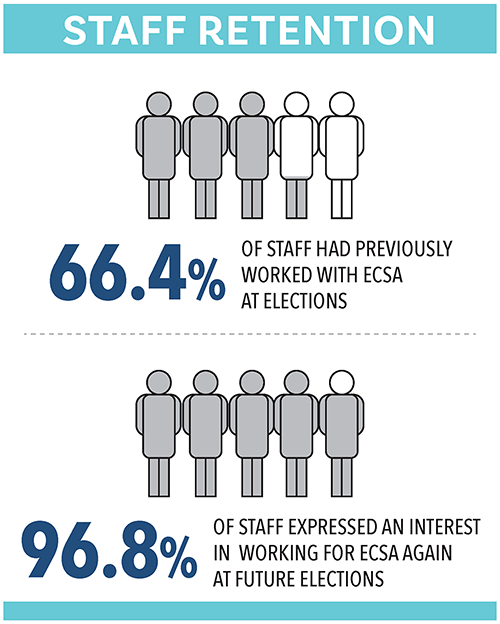

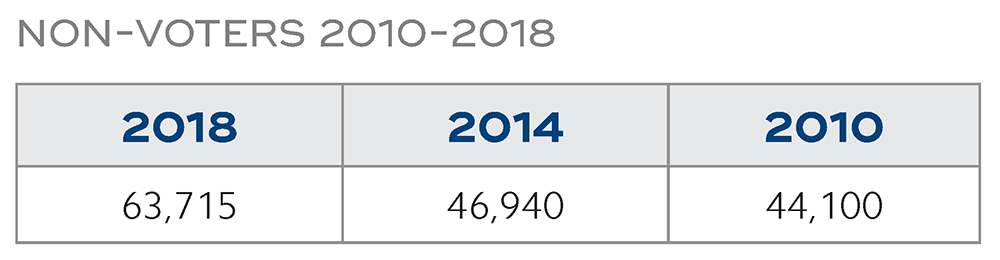

ENFORCEMENT OF COMPULSORY VOTING

One of ECSA’s key tasks in the wake of a State Election is to follow up those electors who appear not to have voted. With the record rate of abstention at the 2018 State Election, the number of non-voters increased significantly. While this abstention can be partly attributed to the increase of the electoral roll through automatic enrolments and enrolments for the 2017 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, reduced youth participation was also a major factor.

Under section 85 of the Act electors who appear to have failed to vote at an election are issued a notice within 90 days of polling day, giving them an opportunity to provide a valid reason as to why they did not vote. In June, notices were issued to 63,715 electors, up from 49,640 in 2014. Of those, 37,480 either failed to respond to the notice or provided an unacceptable reason for not voting and in July were issued with a $70 expiation notice.

Expiation reminder notices were subsequently issued in late August to 27,942 electors who had failed to respond previously, requesting payment of $125 by 25 September, the due date for expiating the offence.

In November 2018, 23,009 expiation notices were sent to the Fines Enforcement and Recovery Unit for enforcement.

BALLOT PAPER AUDITS

After each election ECSA conducts detailed audits

of ballot papers to analyse informality, ticket voting

and compliance with how-to-vote cards. This is an

important quality control measure to ensure the

accuracy of our counting procedures and identify

any improvements that need to be made to manuals

and training.

A detailed breakdown of the findings of the ballot

paper audits will be provided in ECSA’s stand-alone

2018 Election Statistics Report after analysis has

been completed.

Key highlights from the raw data include:

Informality

An analysis of ballot papers for the House of Assembly found 44,821 ballot papers recorded as informal, an increase from 3.1% to 4.1% since the previous State Election. The level of informality ranged from 2.2% for the district of Adelaide to 7.0% for the district of Croydon. The key finding from the audit is that the vast majority (74.5%) of informal ballot papers were cast intentionally by voters, with 42.4% left blank, 24.0% containing marks and messages but no preferences, and 7.9% containing dismissive numbering. Only 23.5% of informal ballot papers appear to have been cast unintentionally.

In the Legislative Council election, 44,497 ballot papers were recorded as informal, an increase from 3.9% to 4.1% since 2014. Informality ranged from 2.4% for electors in Bragg and Waite to 6.4% for those voting in Ramsay. In the audit of 14,736 informal ballot papers from a sample of 17 Legislative Council divisions, the key finding again was that the majority (68.2%) of informal ballot papers had been cast intentionally by voters, with 45.7% left blank and 22.5% containing marks or messages. Of the 31.3% of ballot papers which it is assumed were unintentionally informal, two thirds were cases of informality below the line, particularly incomplete preferences or multiple first preferences indicated.

How-to-vote (HTV) card compliance

In the 17 districts audited, four out of the 91 candidates running did not lodge an HTV card. The audit of ballot papers for those candidates who lodged an HTV card found that overall, 37.7% of all formal ballot papers were consistent with HTV cards, compared to 42.8% in 2014, and 42.1% in 2010.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

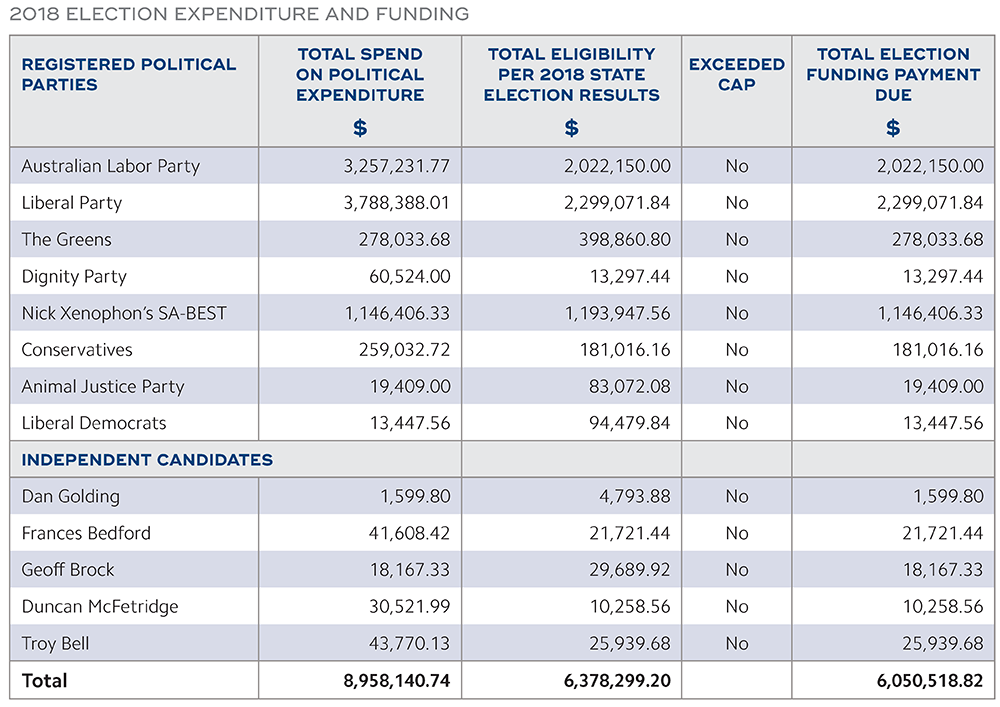

Election funding

Another important task following the State Election was for ECSA to reimburse eligible electoral participants who had participated in the election funding scheme.

The 2018 State Election was the first time that electoral participants in a South Australian election had the opportunity to receive public funding. This scheme is covered by Divisions 4 and 6 of Part 13A of the Act and allows for a reimbursement of political expenditure for eligible participants who keep within the expenditure limits set out in the above divisions.

Following on from the results of the 2018 State Election, 197 candidates qualified for election funding. Of these candidates, five were independent and the remainder endorsed by eight registered political parties.

Based on the political expenditure disclosed in the Capped Expenditure Return lodged by these candidates (or their agent where applicable), no candidate exceeded the caps set out in s130Z of the Act and therefore no penalties were applied to the payments.

Payment is legislated to be made in the period ending 120 days after polling day, and all payments were made within this timeframe.

Lodgement of disclosures

During the designated period of an election, the following returns are required to be lodged with high frequency:

- Political Party Return

- Associated Entity Return

- Third Party Return

- Candidate Campaign Donation Return

- Candidate Group Campaign Donation Return

The designated period for the 2018 State Election commenced on 1 January 2018 and ended on 16 April 2018. The lodgement schedule for the designated period included 12 return periods with stipulated return due dates.

The disclosure threshold applicable during the 2018 State Election was $5,191. Stakeholders are only required to start lodging returns upon commencement of their disclosure period which varies for different stakeholders. For more information on the different disclosure periods, please refer to the relevant guides on the funding and disclosure section of ECSA’s website (e.g. the Third Party Guide and Candidate Guide).

In addition, stakeholders who incurred more than $5,191 in political expenditure during the capped expenditure period (1 July 2017 to 16 April 2018) were required to lodge a Capped Expenditure Period Return to report their expenditure. Participants in the election funding scheme also needed to lodge this return in order to claim public funding.

Donors were required to lodge returns to disclose donations of more than $5,191. There were two due dates for donor returns to be lodged, one for donations made up to 31 December and one for donations made during the designated period.

Over $2.5 million in donations were reported for the designated period.

Audits

The election funding, expenditure and disclosure provisions allow the Electoral Commissioner to undertake investigations for the purpose of ensuring that participants have met their obligations under Part 13A of the Act.

ECSA is currently performing three audits to ascertain compliance of electoral participants. These comprise an election funding audit, state campaign account audit and associated entities compliance audit.

The findings from these audits will be presented in ECSA’s report on funding and disclosure to be published later in 2019.

Observations

Since its introduction in July 2015, the funding and disclosure legislation has been amended a number of times to address various issues with ambiguity and the operation of the legislation. However, not all issues have been addressed or remedied.

The 2018 State Election was the first to have a funding and disclosure scheme in operation. It became apparent during the election period that stakeholders found the legislation difficult to understand and comply with. There were complaints that the legislation was too onerous and not fair in the way it operated. ECSA appreciated the difficulties with the legislation and did its utmost to educate and assist stakeholders. Although there were various compliance issues throughout the State Election, ECSA took a collaborative approach, working closely with stakeholders to help them meet compliance obligations.

Some of the difficulties with the funding and disclosure requirements included:

n Administration and compliance

The 7-day return lodgement schedule during the designated period of the election was a major administrative burden for stakeholders and for ECSA. Many independent candidates and minor parties struggled to lodge on time and to understand reporting requirements. ECSA had to repeatedly chase up stakeholders each week for lodgement. ECSA also spent a large amount of time guiding several stakeholders step by step through the various requirements.

Political parties, associated entities and third parties are required to report ‘Receipts’ (income) and ‘Debts’ for the 7-day period. We received feedback from stakeholders that it is nearly impossible for them to comply with these requirements. Some organisations only do their books at the end of the month, have multiple subdivisions or branches and cannot collate all the required information weekly, or their finance person only works part time. There are delays in receiving invoices which results in inaccurate reporting of debts. A large number of amendments were requested because the figures reported in returns were not accurate.

Donor compliance was also a significant issue. Around 40% of State Election donor returns were lodged late. A majority of these late returns were only lodged after multiple follow-ups by ECSA.

ECSA’s limited resources were strained due to excessive work involved with reviewing returns to check compliance, chasing up late lodgements, educating and assisting stakeholders and amending incorrect returns.

n Inconsistencies and gaps in the legislation

The deadline for appointing an agent in relation to the 2018 State Election was at the close of nominations. Some organisations who became third parties after this date were unable to appoint an agent.

2018 State Election third parties ceased being third parties at the end of the election due to an apparent oversight in the legislation. For all other elections occurring after 2018, the general rule is that third parties will retain their third party status until the next election, which means that they will continue to lodge third party returns until the next election.

n Impracticable operation of the legislation

There was considerable feedback that the third party reporting requirements were too onerous and created a barrier to freedom of political communication. The reporting requirements deterred a number of organisations from spending over $10,000 campaigning during the election to avoid being classified as a third party.

If a registered political party or third party receives an amount over $5,000 (indexed) from an organisation, or owes a debt of more than $5,000 (indexed) to an organisation, they are required to provide further details about the organisation, including the names of the directors, trustees or executive committee members. Obtaining and reporting this information was onerous for stakeholders and in most situations, the provision of the information is of little public interest.

There are many other issues with the legislation. ECSA will undertake a comprehensive review of the funding and disclosure scheme in 2019 to determine recommendations for legislative review with a report prepared for tabling in Parliament.